Adapted from Monique Toppin, Cinema and Cultural Memory in The Bahamas in the 1950s. PhD dissertation, University of Stirling, 2019.

A National Star

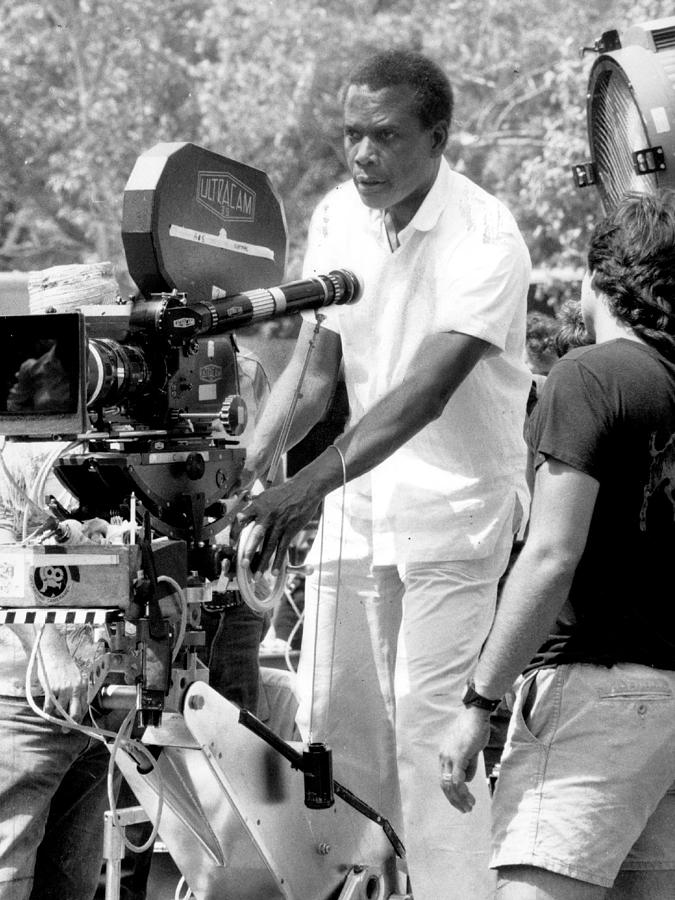

Sidney Poitier emerged as a star in the early 1950s. Although born in the United States in 1927 to native Bahamian parents visiting Florida, he spent the formative years of his life in the Bahama Islands. He returned to the US as a teenager in 1943, worked his way to Hollywood, and was the first Black man to receive the prestigious Academy Award for best actor, for his role in Lilies of the Field in 1964.

It has been suggested that Poitier’s success as an actor and ultimate rise to ‘stardom’ were influenced by his ‘transnational background’. In his delivery, for example, he had “attained his distinctive vocal articulation as a result of years adapting his British-tinged Bahamian English to the United States” (Meeuf & Raphael, 2013). Poitier was cast in roles that were somewhat different to those of Black Americans. He was the ‘other’ type of Black American, not the ‘Tom’, ‘Coon’ or ‘Buck’. Donald Bogle labelled him a “hero for an integrationist age”, considering him the poster-boy for both white and black America:

Poitier’s ascension to stardom in the mid-1950s was no accident…In all his films he was educated and intelligent. He spoke proper English, dressed conservatively, and had the best of table manners. For the mass white audience, Sidney Poitier was a black man who had met their standards. His characters were tame; never did they act impulsively, nor were they threats to the system … Poitier was [also] acceptable to black audiences. He was the paragon of black middle-class values and virtues … Black Americans were still trying to meet white standards and ape white manners, and he became a hero for their cause. He was neither crude nor loud, and, most important, he did not carry any ghetto cultural baggage with him. No dialect. No shuffling. No African cultural past (Bogle, 1973; see also Willis, 2015).

The roles that Sidney Poitier played in the two films remembered by the narrators in my oral history of 1950s Bahamian cinemagoing certainly correspond to the model described by Bogle. In NO WAY OUT (1950) he represented the kind of black man who could easily assimilate into the America of the 1950s; and even in THE DEFIANT ONES (Stanley Kramer, 1958), a prison adventure drama where he is pictured shackled to a white prisoner (Tony Curtis), he proved his responsible and reliable character in remaining loyal and faithful in his undying allegiance to his ‘white friend’ (Strachan, 2015).

Bahamian memories of Poitier

In a 2007 interview with Sir Sidney Poitier, he shares some of his thoughts on The Bahamas, detailing how his upbringing helped him to frame his life in the United States:

“When I went to Florida for the first time, I was being introduced to an entirely new culture. It was so different from Cat Island and Nassau. Though there was segregation in Nassau – for instance, I could not go to the Nassau Theatre – the impact of race was not as intense or impressive because there was a majority population of black people. British colonialism required that you train a native constituency to administer rules: the subjects of the British Empire far outnumbered the English themselves. Colonial administration meant that they had to have black policemen” (Campbell, 2007).

Sidney Poitier’s impact on individual Bahamians is charted in my oral history interviews. One of his relatives, Daniel, was one of the narrators who remember the movie NO WAY OUT, and the night that it opened in a theatre in Nassau:

“We went there…[his] mother was the recipient, she was the big one … everyone wanted to know Mrs. Poitier… everyone wanted to meet Mrs. Poitier … Sidney’s mother. And we went in, and when Sidney picture came out, man, that place, people, and … we were so proud, (chuckles) you know, we went and they presented her with a big bouquet. They had a car for us, back and forth, oh yeah, they took care of us. Sidney’s first movie, ah man, he was the king (chuckles). Everybody, Sidney Poitier, Sidney Poitier, when that over, maybe another couple of months another Sidney Poitier movie out.”

Image sources: United Archives GmbH/Alamy

Censorship: NO WAY OUT (1950)

Sidney Poitier’s first major motion picture, NO WAY OUT (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1950) was about a black doctor working in a hospital in New York in the early 1950s who treats a white man who died under his care. The film included scenes of racial tension, and a race riot. The possibility of its being shown in the Bahamas was unthinkable for the then white minority rule government. The Citizens’ Committee was a group formed in 1950 and comprised of middle-class non-whites whose primary concern was the confrontation of racial issues in the colony (Craton 1998; Foulkes, 2006). In an open letter in The Citizens’ Torch to the Governor of the Islands, matters of race and censorship were addressed:

The United States, during most of its existence has been faced with the problem of race discrimination and injustices. In very recent years the problem has played on the conscience of this great country, and so impelled by its doctrines of democracy, it has been making valiant efforts to eliminate this blot from its fair history. One among many methods it chooses to do this is through that great medium of education, the moving picture screen, and consequently the film companies have been producing pictures which show the foolishness of this business of hatred and discrimination. One such picture was NO WAY OUT, a film starring a young Bahamian actor playing a stellar role and preaching a strong doctrine against the evils, injustice and demoralizing effects of race hatreds. The censor committee has over and repeatedly refused to allow these pictures to be shown here in Nassau, and true to their irrational custom refused permission for ‘No Way Out’ (Eneas, 1951).

There was also opposition to the film in the United States, where films were often censored at the state level “on the grounds of miscegenation, social equality, and racial strife” (Scot, 2014). The movie was banned in Chicago on the basis that it would disturb the peace and was only released after the deletion of a scene in which ‘Negroes’ were shown preparing and arming themselves for a riot. One of my narrators, Alan, a young black engineer…remembers similar tensions surrounding bigotry both on the screen and with the white owner of the four major cinemas:

The Bethel Brothers fought the movie; Sidney Poitier’s first movie; they fought it, said it was too racial; and they allowed, but did some cutting out of it before it showed; I don’t think it ever went to the Savoy.

The film was, as Alan recalls, ultimately shown in at least one cinema in Nassau, but this was only after the Citizens’ Committee applied pressure on the government to allow its screening. The clarity of his memories shows compellingly how Sidney Poitier’s link to this small group of islands in the British Empire was without doubt a matter of pride for those on the island who were aware of his Bahamian heritage.

Monique Toppin, 2021.

References and further reading

Donald Bogle, Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, & Bucks. An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Films, Updated and Expanded 5th Edition, Bloomsbury, 2016

Christian Campbell, ‘”Island Boy”. An Interview with Sir Sidney Poitier,’ Callaloo Vol.30, no 2, pp. 483 – 486.

Michael Craton & Gail Saunders, Islanders in the Stream. A History of the Bahamian People. Vol.2. From the Ending of Slavery to the Twenty-First Century. University of Georgia Press, 1998, esp. pp.305-310.

Stanley Crouch, ‘Comes a Hero. The Fundamental Principles of Sidney Poitier,’ Film Comment Vol. 47, no. 2 (Mar, 2011), pp. 34-37.

C.W. Eneas, C. W.,’ Editorial,’ The Citizen’s Torch, February 1951, pp. 1-4.

Arthur Foulkes, ‘Defining Censorship and Decency,’ The New Black Magazine. n.d.

Aram Goudsouzian, Sidney Poitier: Man, Actor, Icon. University of North Carolina Press, 2004

Lester J. Keys & André H. Ruszkowski, The Cinema of Sidney Poitier. Barnes, 1980.

Russell Meeuf and Raphael Raphael, eds., Transnational Stardom: International Celebrity in Film and Popular Culture. Palgrave, 2013.

Ellen C. Scot, Cinema Civil Rights: Regulation, Repression, and Race in the Classical Hollywood Era. Rutgers University Press, 2015

Ian G. Strachan, Poitier Revisited Reconstruction a Black Icon in the Obama Age. Bloomsbury Academic, 2015

Sharon Willis, The Poitier Effect: Racial Melodrama and Fantasies of Reconciliation. University of Minnesota Press, 2015